The Cost Of Everything – The Value Of Nothing

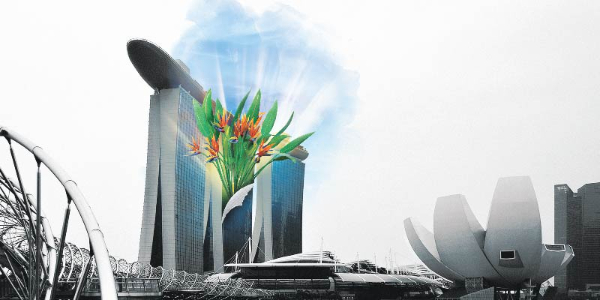

This glimpse of the future was crafted by Michael Nolan and Jessica Holz

How much is it worth to have sugar gliders swooping through the streets of Melbourne, Australia? Recent research shows that wildlife thrives in urban settings if aspects of their natural habitat are left intact by human development. Gliders could attract tourists, control insects and better balance the environment, perhaps improving life in Melbourne.

Is it possible to imagine a scenario where the dividend return to investors was improved in those organisations that preserved ecosystems rather than destroyed them? At the moment, there is no financial reason for developers to preserve natural ecosystems, mainly because there is no asset-valuation of nature.

What if we could establish 'assets' out of ecosystems? Could we save our biosphere by asking developers and owners to invest in it?

A new value system

In response to fast-growing populations, accelerating resource-usage and rapidly expanding middle classes, the United Nations developed 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, covering issues such as poverty, gender equality and education. Many of the SDGs are related to the environment: 6) Clean Water and Sanitation; 7) Affordable and clean energy; 12) Responsible consumption and production; 13) Climate Action; 14) Life below Water, and 15) Life on Land.

The SDGs are a good start but they are not perfect. Since their inception, the loss of species has been accelerating, while the planet is forecast to keep warming and water security remains a problem for large parts of the world.

The annual SDG report by the United Nations last year found that even though progress has been made in some areas, these advances were offset by the "growing food insecurity, deterioration of the natural environment, and persistent and pervasive inequalities".

There is an urgency in finding a workable approach. We know human actions are destroying habitat and directly contribute to species decline and extinction. The scale of this loss is mind boggling. For instance, the WWF Living Planet Report 2020 found that global wildlife populations fell by 68 per cent on average, between 1970 and 2016, and some Australian species populations plummeted by up to 97 per cent.

Why? The answer is: at the moment, other priorities, typically economic ones, prevail. Something has to change. We need to value what we might lose, while also looking for unconventional ways to recognise the value and benefits from healthy natural systems.

Biodiversity's inherent asset value

Natural ecosystems, flora and fauna, have their own intrinsic value. However, their broader value is to promote the stability of ecological systems on which humans depend.

There is a long-established link between spending time in nature and our psychological well-being and health. And lately, the link between biodiversity loss and increased burden of zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19, has a chilling relevance.

The irony is, humans are almost wholly responsible for the current wave of global extinction, but we don't fully realise the consequences of our actions until they happen.

Psychologist and economist Per Espen Stokes explains that this happens because humans experience several 'brain challenges' when dealing with the "abstract, slow moving, invisible threat of climate change", so we tend to distance ourselves from it. Out of sight, out of mind.

He suggests that to overcome this, we have to reframe and be more creative in the way we communicate the consequences of climate change. Otherwise, it may result in 'apocalypse fatigue'.

The engineering profession is involved in most of the drivers of extinction, and many of us consider it our role to provide the advice and capability that allows the built environment to have little or no impact on the natural environment. How then can this be achieved?

Incentivising developers of the future

Unfortunately, good intentions from ethical professionals can only do so much – the next step must give the environment a hard valuation.

Properties with wetlands, for example, aren't that attractive for land buyers and real estate agents, since it limits what you can build on the land and will require an extensive and expensive process merely to get a permit to develop it.

Although wetland features can be found in many golf courses as it adds to the ecological value and playing challenge for golfers. Imagine if developers could claim the wetland ecosystem as an asset, carried on their balance sheet at an agreed value? What was once a problem is now an incentive for developers and organisations to follow the existing contours of the land and retain the wetland system.

This can also help golf resorts and developers, who will preserve these wetlands to position their brands as environmentally friendly and gain more customers. In fact, country clubs in Florida started to become more eco-friendly after residents and customers made their case to embrace sustainability.

The next iteration of the UN's SDGs is likely to include a goal based on this sort of incentive: ecological valuation and establishing financial metrics that evaluate the 'system' benefit of ecosystems to the biosphere, not only the 'land value'.

In establishing ecosystem valuation, we have to understand 'resilience value': the system-value that a rainforest, a wetland or a species provides to the connected ecosystem. Such evaluations have existed in the academic realm for a long time, but not in the commercial realm. What is valuable to a scientist is not measured by a bank or investor, unless there are prohibitions on land-use.

Commercial developers have learned there is value in developing office buildings with a rating systems accreditation. The higher the rating, the more attractive it is to tenants who have a sustainability agenda and, consequently, the higher the rent that can be achieved.

Some environmental purists are sceptical of this focus on monetary value. However, when you have a common good with few controls – like the ocean – no one will value the health of the ocean.

Creating value from natural capital is already a success. Australia's carbon credit system values the reduction and storage of carbon dioxide and makes a financial instrument of it. A similar approach to biodiversity stewardship could also recognise billions on the books of large ecosystem owners.

Although some parts of the world such as New South Wales in Australia, the US and the UK have developed biodiversity offsets, this does little to change development decisions because the market price is low compared to the real value of natural assets.

Returns from biodiversity services already exist, for instance the free water-filtration services offered by a wetland. But we don't value it, so wetlands are bulldozed and drained.

Research into climate change and species extinction mostly focuses on what is lost – not the financial value of retention, which is the value that will urge owners and developers to keep and enhance the ecosystems.

Engineering a healthy planet

Why are engineers supporting a financial solution to an environmental problem? Primarily because we work at every level of the value chain, from government advice and corporate design strategies, to on-the-ground solutions with construction companies.

Just as the financial sector has recognised it has to build sustainability and biodiversity into the world of capital, many engineering firms know the innovation and solutions to make it all work will come from their profession. We know if we can design an environmental valuation regime in the right way, the developer will be incentivised to design a golf course that retains the wetland.

One thing COVID has revealed is that many hard rules are simply habits that can be changed. We can use this COVID shock to re-evaluate the rules of the world we live in and generate value from the ecosystems that sustain us all.

Today, it's a sugar glider returning to the trees of Melbourne; tomorrow, it could be a healing planet that pays everyone a real dividend.

Aurecon’s award-winning blog, Just Imagine provides a glimpse into the future for curious readers, exploring ideas that are probable, possible and for the imagination. This post originally appeared on Aurecon’s Just Imagine blog.

NIWA: Students Representing New Zealand At The ‘Olympics Of Science Fairs’ Forging Pathway For International Recognition

NIWA: Students Representing New Zealand At The ‘Olympics Of Science Fairs’ Forging Pathway For International Recognition Coalition to End Big Dairy: Activists Protest NZ National Dairy Industry Awards Again

Coalition to End Big Dairy: Activists Protest NZ National Dairy Industry Awards Again Infoblox: Dancing With Scammers - The Telegram Tango Investigation

Infoblox: Dancing With Scammers - The Telegram Tango Investigation Consumer NZ: This Mother’s Day, Give The Gift Of Scam Protection And Digital Confidence

Consumer NZ: This Mother’s Day, Give The Gift Of Scam Protection And Digital Confidence NZ Airports Association: Airlines And Airports Back Visa Simplification

NZ Airports Association: Airlines And Airports Back Visa Simplification Netsafe: Statement From Netsafe About Proposed Social Media Ban

Netsafe: Statement From Netsafe About Proposed Social Media Ban